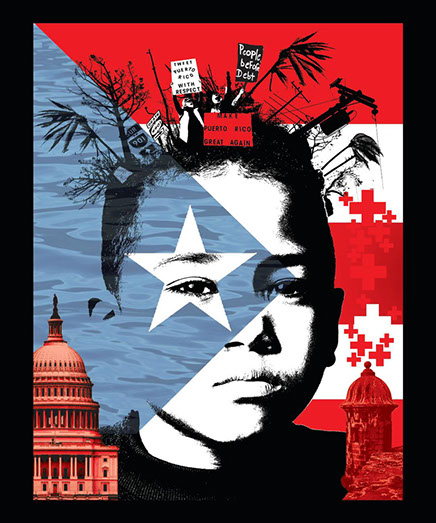

Political Storm

Puerto Rico is far from Recovery

The aftermath of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico is sobering: 60% of the island lost its vegetation, some beaches, parks, and natural trails remain closed, the island has accumulated a record amount of debris with diminished landfill capacity, nearly 300 historic properties have significant damage, mold and mildew threaten many records, and water and electricity availability remain an issue months after the devastating storm swept through last September. But the economic impact on an already weakened island economy could top tens of billions of dollars and could be felt for decades, according to some economists.

For island residents, it has been nothing short of a nightmare, San Juan public relations specialist Charlyn Gaztambide Janer tells LATINO Magazine: “People are angry, sad, impatient. It’s different than the usual happy people from before. I’ve had to resign from a part-time job because they cut the hours and I was actually spending more on gas than what I was getting paid. We are fed up and worse off than before the hurricane.”

The response by both the local and federal governments has been criticized as slow and inefficient. President Trump at one point compared the disaster to the devastation in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, saying that what happened on the island wasn’t as bad as Katrina. His sole visit to the island after the storm was panned as tone deaf, and many Puerto Ricans complained that federal officials and the U.S. Congress were not paying as close attention to the island – with its nearly four million U.S. citizens – as Florida and Texas, which were also battered by the storm.

at one point compared the disaster to the devastation in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, saying that what happened on the island wasn’t as bad as Katrina. His sole visit to the island after the storm was panned as tone deaf, and many Puerto Ricans complained that federal officials and the U.S. Congress were not paying as close attention to the island – with its nearly four million U.S. citizens – as Florida and Texas, which were also battered by the storm.

San Juan Mayor Carmen Yulín Cruz clashed with Trump, who criticized her in a series of tweets and comments on social media. The mayor, who called the storm’s aftermath on the island “a humanitarian crisis,” remained unfazed and called the president a “miscommunicator-in-chief” and also slammed his comments that the federal budget was taking a hit because of the damage on the island as “insulting”. Yulín Cruz has figured prominently in U.S. media outlets, continuing to criticize the president and appealing for more attention and aid to the island, at one point saying at one point, “I cannot fathom the thought that the greatest nation in the world cannot figure out logistics for a small island.” Her activism earned her a spot as a finalist for TIME Magazine’s Person of the Year.

Part of the problem and perception of neglect, says Lorraine Cortés Vázquez, former New York Secretary of State and Senior Advisor to New York Mayor Bill de Blasio, has been a lack of basic information: “The information many non-Puerto Ricans have about Puerto Rico is very minimal, so much so that in the mainstream, many didn’t know that Puerto Ricans were citizens until this disaster.”

When Hurricane Maria hit, its punches were felt by Puerto Ricans on the mainland as well. With their numbers growing significantly in recent years – there are more Puerto Ricans living in the 50 states than on the island – they have been using their increasing clout and deep ties to the island to rally and mobilize money and supplies in support of families and friends. Some of the efforts are well-known, such as high-profile celebrities pledging millions in aid and delivering items to the island, while several groups have formed to mobilize as quickly as possible.

Washington, DC-based chef José Andrés stood out by getting together with the group Chefs for Puerto Rico and other volunteers to cook meals for displaced residents, at one point cooking some 100,000 meals a day throughout the island and bringing supplies to others on the island so they could feed more people. José Andrés had founded the nonprofit World Central Kitchen shortly after the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, which works to combat hunger, and said he had arrived in Puerto Rico shortly after the hurricane because there was “no plan” to feed the people – and he ended up opening the world’s largest kitchen within in a week of arriving.

Recently, more than 400 advocates for Puerto Rico packed a conference room at the University of the District of Columbia for a mini-summit in the nation’s capital to discuss strategies to keep the issue of post-Hurricane Maria recovery on the front burner in Congress. The island is still struggling with rebuilding amid a pre-existing economic crisis, and participants at the gathering sponsored by the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College in New York and the National Puerto Rican Agenda, among other groups, said that while the so-called “diaspora” – Puerto Ricans living outside the island – mobilized in the immediate aftermath of the storm, it was imperative to unite behind helping the island for the long term. “The diaspora is critical in terms of advocacy, advocating for Puerto Rico on Capitol Hill. The diaspora needs to take matters into their own hands,” says Frances Colón, founder of the community organizing group Cenadores PR and a former Senior Advisor on Science and Technology to then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

“There comes a time in history where we have to say aquí se acabó [enough is enough],” adds Ambassador Mari Carmen Aponte, a Puerto Rico native and former Secretary of State for Western Hemispheric Affairs during the Obama Administration. “The situation in Puerto Rico is dire and the legislative situation is entirely awful, and we’re going to need all the involvement from all the community at all levels.”

Flavio Cumpiano is a lawyer in Washington, D.C. who has been extensively involved in post-hurricane recovery efforts. “There’s the peril of disaster fatigue, that when something happens people immediately get involved and then it tapers off and the attention wanes, but there is still a lot of need in Puerto Rico and it’s not going to get better any time soon,” he said “It’s going to be a long haul.”

Cumpiano cites several organizations that continue with hurricane relief efforts, including Friends of Puerto Rico and Vieques Love, the latter helping the island community off the east coast of the main island. “Vieques is an island of an island and was affected even more. The people of Puerto Rico know they can’t wait around for the government to do something, and instead of relying on the government they find a way to get things done,” Cumpiano adds. Another group is Teen4PR, started by several NYC teens to raise money for various organizations on the island, and there’s PrxPR.org, founded by several Latino professionals, including Telemundo anchor María Celeste Arrarás. Yet another is BoricuActívatEd, a non-profit founded by former Capitol Hill staffers Jennice Fuentes of the government relations group Fuentes Strategies and former Obama administration official Federico de Jesús, principal at FDJ Solutions and a former deputy director of Puerto Rico’s D.C. office. Based in Washington means the group has more readily available access to many who can legislate help, and the organization conducts workshops and trainings on how to lobby Congress, with plans for future sessions in Florida and New York, among other states, to help empower the community.

“Without an active and empowered diaspora, the issues of Puerto Rico can’t be successfully done on Capitol Hill,” says de Jesús. “Those of us in the Washington area are in a unique position because we are in the center of power and media attention, and we can bring attention, from securing supplies to going to Capitol Hill and lobbying for immediate aid, but also [to lobby] for a type of Marshall Plan for the island. It’s important to get involved because human beings are in a desperate situation, and if we don’t do it, nobody will.”

Puerto Rico was already in a slump when slammed by Hurricane Maria, and the economic repercussions continue. Governor Ricardo Rosselló has warned that the island will carry budget gaps for the next four years and won’t be able to pay any of its $72 billion debt until at least 2022. Rosselló estimates that the economy will shrink 11% and the population will drop by 8% next year. He has presented a revised post-storm fiscal plan that assumes Puerto Rico will receive at least $35 billion in federal funds for storm recovery efforts, but those are currently being withheld by the Trump Administration because its position is that the island has enough cash reserves. The plan also includes a proposal to privatize the much-maligned electric utility company known by the acronym PREPA in English. The company has been sharply criticized for its handling of post-hurricane efforts to restore power, including awarding a highly controversial contract to a small Montana company named Whitefish to rebuild the electric grid. The agreement was eventually canceled, but not before much criticism, including from U.S. legislators who held hearings on the contract and slammed the island government for signing it in the first place.

Meanwhile, Governor Rosselló has warned that the island will carry budget gaps for the next several years and won’t be able to pay a dime of its $72 billion debt until at least 2022. Island officials are asking Congress for nearly $95 billion in aid to help in recovery efforts, and while Congress has approved some disaster aid, officials say much more is needed. The $94.4 billion request mirrors the amount Rosselló mentioned in a letter to members of Congress late last year when he outlined what he said were “independent damage assessments” of the funds needed to restore and rebuild, including housing and the island’s infrastructure. Island officials have been asking that Congress consider several changes to the Stafford Act, which details federal natural disaster assistance for state and local jurisdictions.

The Act specifies that critical infrastructure, such as electricity, be restored to its pre-disaster mode, but the Puerto Rico government considers their utility system to be outmoded and want to rebuild it, rather than restore it. Congress has approved some disaster aid, but it includes loans to the island rather than grants, and island officials say it’s not nearly enough. Rosselló, a supporter of statehood for the island, has said that the island would be treated better by the federal government if it were a state, and recently formed a commission to lobby for the island to become the 51st state -- but that has been criticized as poor timing by even those who support statehood, including Republican Senator Marco Rubio of Florida who told the island daily El Nuevo Día:

“If I were the governor of a state or territory that does not have power, I would spend more time there. At this moment, frankly, we don’t have the votes [for statehood] in the Senate.”

Gaztambide Janer concurs: “Right now It’s a big waste of time. They need to work on fixing things here. There are still people without a roof over their heads. Rubio is right.”

Congress, mired of late in government shutdowns and issues like DACA and gun control, has also been more focused on clearing its calendar to concentrate on the upcoming midterm elections, when the entire House of Representatives and several key Senators are up for reelection. And that, say some political observers, is where the recent migration of Puerto Ricans leaving the island post-hurricane could play a crucial role, and bring more attention than any statehood commission could.

Rosselló estimates that the economy will shrink 11% and the population will drop by 8% next year. According to the Census, Puerto Rico is the only majority Latino jurisdiction that has actually lost population – all others have seen gains. Puerto Ricans are the second-largest group of Latinos in the United States, surpassed only by residents of Mexican origin. A recent Pew Research Center report finds that in just a ten-year period from 2005 to 2015, the number of Puerto Ricans living on the mainland grew from 3.8 million to 5.4 million.

Many of those island residents have landed in Florida, over 300,000 according to some estimates, which political observers say could mean a seismic change in the state politically. Puerto Ricans on the island do not vote for members of Congress or for U.S. president, can do so once they establish residency in one of the 50 states. Florida has a Puerto Rican population of nearly one million, and a study by the Hispanic Federation and Nielsen estimates that the Sunshine State’s Puerto Rican residents could by 2020 surpass the Cuban American population. While the Cuban American vote has stereotypically been identified with the Republican Party, many assume that Puerto Ricans would lean more toward the Democrats, while others say they represent a crucial and powerful swing vote that neither party can ignore, especially by the Democrats if they wish to take back both houses of Congress this fall.

“They’re not automatically liberal voters,” says de Jesús. “Liberals and Democrats who assume that newly arrived Puerto Ricans in Florida are automatically in the ‘D’ column do so at their own peril. Puerto Ricans in Florida are swing voters and therefore should be courted with much more attention and resources by Democrats in order to ensure a longer-lasting allegiance from Puerto Rican voters in Florida.”

Patricia Guadalupe