Why are Central American Refugees Here?

Roots of the Problem

A nine-year old Honduran boy, identified in court records only as J.S.R., traveled thousands of miles with his father to live in the United States, driven to make the journey by the horrific violence at home – his grandparents had been murdered and the body of a stranger was left in his backyard.

That boy was one of thousands of children from the “Northern Triangle” as Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala are known, who were separated from parents seeking asylum in the United States this year.

The exodus from those countries, all rocked by civil wars in the 1980s that left a legacy of violence and fragile institutions, is expected to continue, despite the Trump administration’s hardline attempts to staunch the flow, a policy that sent the Honduran boy to a shelter in Connecticut and locked up his father in Texas.

While immigrant family separations have been the subject of scorching criticism and international outrage, the reasons those families have risked lives and often spent all they had trying to cross the U.S. border are not widely understood and the result of huge problems that are extremely difficult to solve, according to foreign policy experts

According to the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), the number of asylum seekers from the Northern Triangle reached 110,000 in 2015, a five-fold increase from 2012. Since 2015, the numbers of migrants has fluctuated, and perhaps dropped a bit since then, but the reasons for the migration have not changed.

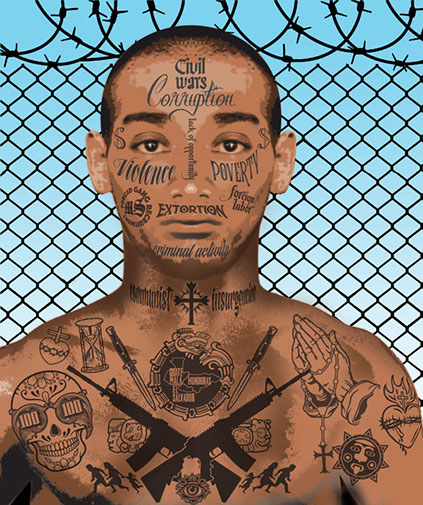

These refugees cite violence, forced gang recruitment, and extortion, as well as poverty and lack of opportunity, as their reasons for leaving. While Belize, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama have reported a sharp increase in flows from the Northern Triangle since 2008, most migrants are passing through those neighboring countries to try to settle in the United States.

The CFR said that in 2015, the latest year for which data is available, as many as 3.4 million people born in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras were living in the United States, more than double the estimated 1.5 million people in 2000. About 55 percent of them are undocumented.

The Honduran boy whose grandparents had been murdered was reunited by a federal judge’s order with his father, who was released from detention and paroled for six months, giving him a chance to seek asylum. But most migrants from the Northern Triangle won’t be as lucky. The Trump administration is detaining and trying to deport all those who cross the border as soon as possible and is trying to make it more difficult for victims of domestic or gang violence to qualify for asylum.

There’s evidence the hardline policies have slowed migration, but they haven’t stopped it.

“I personally don’t think that the answer to the problem of migration is at the U.S.-Mexican border,” said Eric Olson, deputy director of the Wilson Center’s Latin American Program. “The Trump administration thinks “if you make it tough enough, people will stop coming. But that’s not going to work. The real solution lies in Central America.”

El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras consistently rank among the most violent countries in the world. The murder rate in El Salvador, for instance is 81.1 people per 100,000, compared to about 16 per 100,000 in Mexico.

Extortion and corruption in the Northern Triangle are also rampant. A 2015 investigation by Honduran newspaper La Prensa found that Salvadorans, Guatemalans and Hondurans pay an estimated $390 million, $200 million, and $61 million, respectively, in annual extortion fees to organized crime groups. Extortionists primarily target public transportation operators, small businesses, and residents of poor neighborhoods, according to La Prensa, and attacks on people who do not pay contribute to the violence. Olson said widespread corruption in politics, the police and the judicial system adds to the instability caused by gang violence and lack of opportunity in the Northern Triangle.

The troubles began in the late 1970s, when civil wars and communist insurgencies broke out in the Northern Triangle. The United States feared that it would be cut off from the rest of Central America if pro-Soviet governments ran El Salvador and Guatemala, so it backed often corrupt puppet governments and the nation’s elites, who tended to ignore the needs and demands of the working class and peasants. Honduras did not have a civil war of its own, but nonetheless felt the effects of nearby violence. It also served as a staging ground for the American-backed Contras, a right-wing rebel group fighting Nicaragua’s Sandinista government during the 1980s.

“These countries were destroyed by civil war and the United States is partly to blame,” Olson aid. “It’s not like these countries were Switzerland and somehow turned bad.”

The United States was also partly to blame for the growth of gangs in Central America. Mara Salvatrucha, also known as MS-13, the gang President Donald Trump says is invading the United States, originated in Los Angeles in the 1980s and was exported back to El Salvador after federal immigration officials deported a wave of young, criminal Salvadorans.

Trump said these “animals” are flooding across the border and posing with unrelated children as fake families to better their asylum claims. He used the threat of M-13 violence to implement a “zero-tolerance” policy at the U.S. border with Mexico that resulted in the detention of thousands of migrants from the Northern Triangle this year. That policy also resulted in the separation of children from their parents because minors can’t be detained for long periods of time under a court order known as the Flores consent decree.

But of the hundreds of thousands of minors that have come to the United States since 2012, U.S. Customs and Border Protection says only 56 were suspected of MS-13 ties. Nor is the gang growing. The Justice Department said there are about 10,000 MS-13 members in the United States, the same number as there were 10 years ago.

M-13 gang members are concentrated in a few areas of the United States, mostly Los Angeles County and the San Francisco Bay area in California, Washington D.C., Queens and Long Island in New York, Boston, and several cities in New Jersey – including Newark, Jersey City and Elizabeth.

Steven Dudley is the co-director of InSight Crime, a joint initiative of American University in Washington, D.C., and the Foundation InSight Crime in Medellin, Colombia, which monitors and investigates organized crime in the Americas.He said MS-13 and other bloodthirsty gangs “are more social animals than criminal. Their intentions and reasons for entering into the gang are largely social in nature; they’re looking for community,” Dudley said. “Granted, community is constructed around, and reinforced by, things like extreme violence and some criminal activities… but we have to think of these things as social in nature.” To Dudley, the best way to fight these gangs is to create an alternative community to compete with the gang. “We’ve seen that some of the most successful alternative communities are evangelical churches” he said.

At a Wilson Center seminar on what’s driving Central American migration held in June, Emmanuel Abuelafia, the lead economist on Central America at the Inter-American Development Bank, said that it’s not just violence that’s pushing migration, but the lack of economic opportunities and education.

There are other needs, too, that aren’t met at home Abuelafia said, such as a decent health care system.

“They are thinking ‘I cannot send my kids anywhere for school, I cannot get a job,’ so they decide to migrate,” Abuelafia said. “They first migrate internally, then they go north.”

Abuelafia said the IDB is coordinating a region-wide study of migration. But this known now: About 50 percent of the Central American migrants are captured in Mexico, another 40 percent are detained in the United States and only 10 percent are successful in getting across the U.S. border undetected.

Since the George W. Bush administration, the United States has tried in several ways to stem the violence in the Northern Triangle, bring greater stability to the region and slow the northern migration from Central America. Bush focused on fostering the region’s growth and stability by increasing trade and introducing free-market reforms. Through the Millennium Challenge Corporation, a foreign aid agency established by Congress in 2004, his administration awarded hundreds of millions of dollars in grants to Honduras, Nicaragua, and El Salvador. Bush also introduced a security assistance package for Central America and Mexico known as the Merida initiative.

President Barack Obama separated Mexico from the Merida grouping and called the new plan the Central American Regional Security Initiative. It provided more than $1 billion in aid to help the region’s law enforcement, counter narcotics and justice systems. The Obama administration also worked with the Inter-American Development Bank to promote commerce after a wave of unaccompanied minors began arriving in the United States in 2014.

Trump has adopted much of his predecessor’s approach to the region, but has taken a much harder line on immigration policies affecting Central America. Besides imposing a “zero tolerance” policy and trying to limit asylum claims, the Trump administration has revoked the “temporary protected status” designation given immigrants from countries that have suffered hardship.

Within the next few years, nearly 350,000 immigrants from Northern Triangle countries will lose the legal right to live and work in the United States as a result of Trump revoking their temporary protected status. How many will be deported and how many will go home on their own is not known.

Manuel Orozco, director of migration, remittances and development at the Inter-American Dialogue, said there’s another reason for people come to the United States from Central America. The driver is the demand for foreign labor. Orozco says a growing area of the U.S. economy is the real estate and construction industries, industries where many migrants work. About 25 percent of construction workers are immigrants, he says.

The need for domestic workers in the United States is also a draw, Orozco says.Imposing a zero-tolerance policy and deporting Central Americans who now have temporary protected status may slow migration to the United States, but it will also increase the economic woes in the Northern Triangle and remittances decrease.

Remittances alone amounted to $17 billion in revenues to the Northern Triangle in 2015, representing more than 50 percent of the household income for some 3.5 million households in the region.

To Olson, the problems besetting the Northern Triangle are “incredibly difficult” and will take a long time to solve. “it’s more about prioritizing and deciding where the starting point is,” he said. “it’s not about just throwing money at the problem. But,when everything is a problem, it’s hard to know where to start”

He said he would begin fighting the corruption in the Northern Triangle. “If the police and justice system doesn’t work, then we are just whistling into the wind,” he said. One avenue the United States could take is to deny corrupt Central Americans visas to visit the United States and blocking them from doing business or conducting any financial transactions here. “We need to isolate, weaken and sideline these corrupt officials,” Olson said.

Ana Radelat