Showdown in Tejas

Will Latinos Turn Out to Vote?

With the midterm elections on November 6 fast approaching, candidates nationwide are asking the proverbial question: How can I win the Latino vote? To do that, however, candidates must first get Latinos to vote.

With Republican leadership attached to a president who launched his campaign by inciting bigotry toward Mexicans and doubled-down on that position ever since, the prospect seems more likely for Democrats than Republicans. The most recent tragedy of family separation targeting asylum seekers from Central America has only widened the divide.  Logic dictates that Latinos are ripe for the picking by Democratic candidates, but will Democrats know how to finally wake up the sleeping giant? If they do, will they know what to do with a Latino constituency once they’ve won it?

Logic dictates that Latinos are ripe for the picking by Democratic candidates, but will Democrats know how to finally wake up the sleeping giant? If they do, will they know what to do with a Latino constituency once they’ve won it?

According to Pew Research Center projections, a record 27.3 million Latinos are eligible to vote, representing 12 percent of all eligible voters. While Latino voters will figure in nearly all fifty states, Texas may be the one to watch.

Latino Democrats like to say, “You can’t turn Texas purple without brown.” According to the latest estimates from the U.S. Census, Latinos represent nearly 40 percent of the population in the staunchly red Lone Star state. However, there are signs of blue. Former Texas Governor Rick Perry once described Travis County, home to Austin, the state capital, as a” blueberry in a bowl of tomato soup,” but he missed a few more blueberries. While the state is vast, its major urban centers—Dallas, Houston, San Antonio, Austin, El Paso, and Laredo were all won by Hillary Clinton in 2016, according to The Texas Tribune. Plus, Trump’s margin of victory in Texas was smaller than Mitt Romney’s in 2012.

“Texas saw a surge of 400,000 new young registered Latino voters in 2016 and the majority voted for Democrats,” says Cristina Tzintzún, executive director of JOLT, a newly created organization based in Texas dedicated to increasing voter turnout among young Latinos. “It required an extra investment to get them engaged but their votes helped move Texas out of the bottom when it came to voter turnout, to forty-seventh position. Clearly, there’s still much more work to be done.”

Texans are also very young, particularly the Latino voting age population. “In Texas, 67 percent of those under 18 are people of color,” says Tzintzún. “Sixty-seven percent of those over the age of 70 are white while of those under 18, one out of two are Latino and 95 percent are U.S. citizens.”

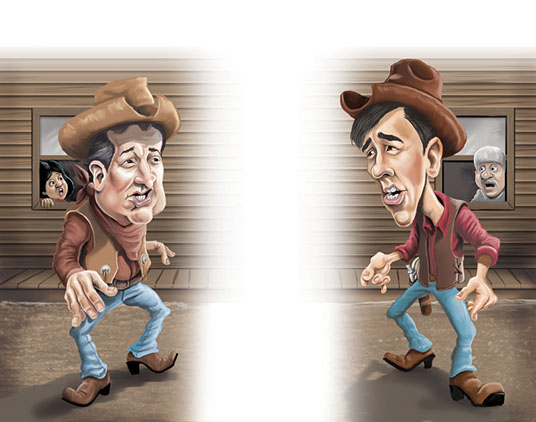

There are two races of particular interest in Texas. For the U.S. Senate, a Latino Republican incumbent named Rafael Eduardo Cruz who chooses to go by Ted, is up against a non-Latino Democrat named Robert O’Rourke, who grew up in a community where Latinos, who make up 85 percent of the population, gave him the nickname “Beto,” will compete for one of two Senate seats. The gubernatorial race involves an incumbent, Greg Abbott, who used his Latina mother-in-law to campaign for him when he first ran in 2016, calling herself his madrina in television ads, and Lupe Valdez, the daughter of migrant workers and a lesbian, who served as the Sheriff of Dallas County for twelve years and who defeated the son of a former Texas governor in the Democratic primary.

A fourth-generation Texan, born and raised in El Paso, O’Rourke played in a punk rock band, attended Columbia  University, and began a tech start-up before serving on the City Council and unseating an eight-term Latino congressman, Sylvestre Reyes, in 2012. He’s committed to not accepting funds from political action committees and even submitted a bill in Congress to make it so. Currently, he and Cruz are neck and neck in the polls. If elected, he would be the first Democratic senator from Texas in twenty-five years.

University, and began a tech start-up before serving on the City Council and unseating an eight-term Latino congressman, Sylvestre Reyes, in 2012. He’s committed to not accepting funds from political action committees and even submitted a bill in Congress to make it so. Currently, he and Cruz are neck and neck in the polls. If elected, he would be the first Democratic senator from Texas in twenty-five years.

Beto, as campaign ads refer to him, is adopting a strategy used by another outgunned Democratic candidate for U.S. Senate, Victor Morales, who ran against Phil Gramm in 1996 and won 44 percent of the vote. Unlike O’Rourke, Morales was considered an upstart, defeating the favored Democratic candidates in the primary and as a result, received neither the blessing of the Texas Democratic Party nor the financial and political support he needed. Undaunted, Morales traveled in his white pick-up throughout the state. Similarly, O’Rourke has been to all 254 Texas counties and to many small towns that get ignored like Weslaco or Del Rio. He’s well aware of the difference Latino voters will make in November.

“Latinos comprise more than 40 percent of the population in Texas so the Latino voting bloc is almost indistinguishable from Texas at large. It’s everything.”

If elected, he says he’ll focus on the issues of greatest concern to Latinos, education, healthcare, and immigration, where he thinks Texas can take the lead on reform. “I’m from one of the safest cities in the country and it’s a city of immigrants,” O’Rourke asserts.

In response to the concerns voiced by Tzintzún and Reeves, he would not share the dollar amount of what he’s spent in the Latino market but offered that all his campaign messages, including rallies, are bilingual and many of his high-level staffers are Latino including Ana Castañon, Deputy Communications Director, and Senior Advisor Gilberto Ocañas.

Texas is also poised to send it’s first Latinas to Congress, Veronica Escobar who is running in the seat vacated by O’Rourke, and state senator Sylvia Garcia, running for House District 29 in Houston.

While both parties remain befuddled over how to energize Latino voters, those in the trenches offer that the solution is simple, time and money (or a lack thereof).

Launched in 2004 ahead of the 2008 presidential election, Voto Latino has been in the trenches with young Latino voters, trying to get them energized. The main issue, says COO Jessica Reeves, is that the level of investment to get Latino voters energized has been way below budgets used to appeal to other groups. Campaigns are tactical rather than strategic, and candidates only seem to think of Latino voters when they decide to run, and not before. Once they do, candidates simply dump all their funds into Spanish-language television as a one-stop shop, ignoring the fact that only a certain percentage of Latino voters may be watching.

“But even the money put into Spanish language media is still a much smaller percentage than what is given to reaching other constituencies,” says Reeves. “They’re still underinvesting in Latino voters, which supports the misconception that we don’t vote. It’s a self-perpetuating myth, perpetuated by the lack of a grassroots effort to reach all Latinos.”

Tzintzún agrees, “It’s a major mistake to think we only speak Spanish. The research we did among 18–45 year olds revealed that 40 percent spoke English primarily or exclusively. The other real mistake they make is thinking that we’re single-issue voters. Immigration is big for young Latino because 53 percent under the age or 30 have a parent who is an immigrant, but the number one issue is healthcare.”

Ocañas adds that the lack of successful efforts has made it hard to know what works for Latinos. “If you do the same thing, hold rally after rally, the same people will go because not everyone goes to rallies, and you’ll have the same level of turnout. You have to try something different and long-term, plan two-to-three years down the road. You have to have a stronger message that communicates clearly.”

In 2014, Voto Latino conducted a study of Latino voters to finally answer the question: “What motivates Latino voters?” According to Reeves, the study concluded that more than political party or particular candidate, what entices Latinos to vote is family. If candidates connect issues to family, they can appeal to them. A positive message is also more effective than a negative one, according to the study.

“Latinos are not turning out for a candidate or party but for community and family and for messages that connect family to why they should vote,” says Reeves. “What resonates is for a candidate to be clear about what he or she is for, like the American dream, economic opportunity, access to education, etc. They need to send a positive message that they want to move forward, tying issues and candidates with engaging in voting as a way to support each other.”

Tzintzún also adds that Millennials tend to be more progressive than their parents and grandparents. Candidates who spout anti-Mexican rhetoric were unappealing as well as anti-immigrant or anti-LGBTQ. “This is a progressive generation,” adds Tzintzún. “Candidates need to speak directly to the needs of this generation and understand the culture, there’s a real lack of those candidates.”

As for whether Latinos vote along racial lines, opinions are split. While Tzintzún and Reeves believe issues matter more, Ocañas also believes that when faced with candidates on a ballot about whom they know nothing, Latinos will select a Latino candidate. It has been suggested that having Valdez on the ballot may increase Latino turnout. “You’ll see this a lot in judicial races,” he says. “In the primary, Beto was beaten by Sema Hernandez in several counties in the Rio Grande Valley. I doubt Latino voters really knew much about her but she did have a familiar last name.”

According to Pew, in 2016, 54 percent of Latino registered voters say the Democratic Party has more concern for Latinos than the Republican Party, while 11 percent say the same of the GOP. Now more than ever, says Reeves, the need for engagement is crucial.

“In this climate, there are so many issues,” she adds. “We’re looking for ways to connect, to give a call to action, and find a way to make a change.” As an example, Reeves cites a rally held in Tornillo, Texas at a detention center where children taken from their parents at the border were held. “We followed up on that event with the message that if we want to make a difference, we need to change things in November and hold our elected officials accountable and look for candidates and officials who will help. We need to recognize that the way to change what’s happening is to turnout and vote.”

Valerie Menard