Blessings for Rudolfo

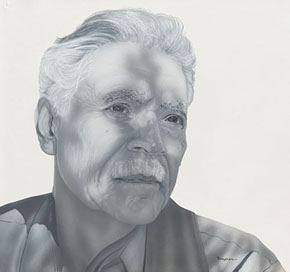

Among Latinos represented in the new acquisitions exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, New Mexico writer Rudolfo Anaya commands pride of place. His portrait is the Smithsonian museum’s first commissioned work depicting a prominent Latino.

“Since there wasn’t a suitable portrait of Anaya that the museum could acquire,” says curator of Latino art and history Taína Caragol, “I thought perhaps we could commission one.” He was an obvious choice to add to the gallery’s growing collection of Latino portraits, she adds. The author of the bestselling Bless Me, Ultima “is a foundational writer of Chicano literature.” When she told him of her plans, Anaya’s response was, “What would my grandmother say!”

Former President Obama awarded Anaya the National Humanities Medal in 2015 for his pioneering stories of the American Southwest that celebrate the Chicano experience. In choosing him for the first Latino commission, Caragol says “I wanted to exhibit his portrait to bring visibility to him and his work.” She also admits to having been concerned about getting the portrait while Anaya, now 80 years old, could see it. In fact, Anaya visited the portrait gallery, unannounced and unheralded, to see it displayed in a museum dedicated to the presidents, generals, scientists and artists who have had significant national impact.

Former President Obama awarded Anaya the National Humanities Medal in 2015 for his pioneering stories of the American Southwest that celebrate the Chicano experience. In choosing him for the first Latino commission, Caragol says “I wanted to exhibit his portrait to bring visibility to him and his work.” She also admits to having been concerned about getting the portrait while Anaya, now 80 years old, could see it. In fact, Anaya visited the portrait gallery, unannounced and unheralded, to see it displayed in a museum dedicated to the presidents, generals, scientists and artists who have had significant national impact.

Bless Me, Ultima was Anaya’s first published novel and remains his best known. It examines the forces that shape the life of Antonio, a young Mexican-American boy who is a main character in the novel. Through the elderly healer Ultima, Anaya explores the world below the surface of experience that contains his culture’s collective images, symbols and dreams. Despite difficulties in getting it published because of its combination of English and Spanish language as well as its Chicano-centric content, the novel has sold over 300,000 copies in 21 printings. It was adapted as a feature film in 2013. Other of his works include the novels Alburquerque, Zia Summer, Rio Grande Fall, Jalamanta: A Message from the Desert and Shaman Winter as well as plays, poetry, children’s books and works of non-fiction.

To create Anaya’s portrait, Caragol chose another Latino —El Paso artist Gaspar Enriquez, whom she described as “the main portraitist of the Chicano movement.” Although Enriquez had a work included in the Portrait Gallery’s 2016 portrait competition exhibition, he was not represented in its permanent collection. The commission did double-duty, adding both Anaya and Enriquez to the museum’s holdings.

Another reason for choosing Enriquez to do Anaya’s portrait was that they had previously worked together. Enriquez had illustrated Anaya’s book Elegy on the Death of César Chávez. Enriquez’s portrait of Anaya employs his signature style, an airbrushed, almost photorealistic image presented with very little context, usually against a white background. Nonetheless, the essence of where his subjects are from–their heritage and past experiences–is reflected in Enriquez’s portraits. In the case of Anaya, that sense of place is suggested by the shadow of a pear tree in the writer’s front yard that subtly shades his face.

Caragol, who previously curated Staging the Self, an exhibition of Latino self-portraits, as well as a biographical exhibition about United Farm Workers organizer Dolores Huerta, has a plan to add works to the collection that address the influence of various Latino groups.

In addition to Anaya, the new acquisitions on display through most of 2017 include prominent Puerto Ricans such as former San Juan mayor Felisa Rincón de Gautier, community organizer Evelina López Antonetty, writer Piri Thomas, television journalist Geraldo Rivera, poet and political activist Clemente Soto Vélea. Ther’w also a mosaic portrait of social leader and founder of Aspira Antonia Pantoja,

The next new acquisitions display, scheduled for late 2017, is likely to focus on other Latino groups. Caragol’s wish list includes portraits of subjects such as Cuban-born artist Ana Mendieta and novelist Reinaldo Areinas, Texas artist Vincent Valdez and New Mexico land-grant activist Reies López Tijerina.

John Coppola