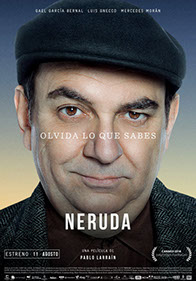

Arresting Neruda

Chilean director Pablo Larraín, the Luis Buñuel of the biopic, has set his pop surrealist eyes on the Chilean poet and political gadfly Pablo Neruda, a man who made no bones about dividing his art between the ever-yoked areas of song and social consciousness.

In Neruda, the titular character (played with winsome and wicked relish by Luis Gnecco) is forked between his powers of obvious persuasion and a world of encroaching oppression. As a popular poet (back when we had those) and as a Marx-minded Senator, this is a scary place to be.

In Neruda, the titular character (played with winsome and wicked relish by Luis Gnecco) is forked between his powers of obvious persuasion and a world of encroaching oppression. As a popular poet (back when we had those) and as a Marx-minded Senator, this is a scary place to be.

Larrain presents a kaleidoscopic commedia dell’arte in which our hero is on the run from the state. It’s a film about the fate of philosopher kings …or the charm in their follies. Before there was ever a thing called underground poetry, we had underground poets. And Neruda is the patron saint of that sect.

It’s 1948 and Neruda adamantly opposes the repressive policies of President Gabriel González Videla’s administration. As a man of letters, he fights with his words and offers his public grievances in a speech in the National Congress. After this, he is threatened with arrest. So, like any right-minded leftist would do, he goes underground. But the life of the mind is only as sated as its psyche provides. And Neruda is restless. Rather than lying low in his new role as enemy of the state, the fugitive keeps finding new ways to pop up and poke fun at the authorities, leaving evidence behind like some Pinko Panther.

As Neruda and his wife Delia (Mercedes Morán) live on the lam, the poet’s wily wits are matched by policeman Oscar Peluchonneau, played with seething gloom by Mexican actor Gael García Bernal, who was Che Guevara in Motorcycle Diaries and received a Golden Globe Award for Best Actor for Mozart in the Jungle. He’s perfect as a foil to Neruda’s swoons into luck and fantasia.

A man of delicious contrasts, Neruda was a fat commie, a raunchy raconteur who could act like a loutish Lothario as well as spin the gossamer beauty of Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair. He was a clown, and very nearly a confidence man. But he was, above all, the living embodiment of conviction. Larraín goes a long way in showing all the uncomfortable contradictions exhibited by this juggernaut of jouissance. In Neruda there is zero judgment if perhaps an undulant level of praise.

Neruda as a character has been dealt with before but not as aptly. Michael Radford’s 1994 movie Il Postino shows the poet in hiding as an aloof, sentimental, but unthinking man who was given to lamentation only after tragedy. And in Mind Walk, wherein Liv Ullman plays a quantum field theorist, Neruda’s “Enigmas” are recited along the beach as a way to more or less halt a three-way with Sam Waterston from happening.

There is no such nonsense in Neruda. Larraín is not trying to teach us but rather reach us, to offer his audience the comfort of the human comedy, as well as the dangers of delight and the eternal struggle against the state.

Roberto Ontiveros